Spotlight on...

Anthropocene

A team of scientists trapped in the Arctic ice. A mysterious discovery that shatters their beliefs about life and death.

Commissioned by Scottish Opera, Anthropocene is the fourth operatic collaboration between composer Stuart MacRae and writer Louise Welsh, and won the award for Large Scale New Work at the 2020 Scottish Awards for New Music. It’s a tense operatic thriller set in a world transformed by climate change, whose suspenseful storyline poses profound questions about sacrifice, exploration and our ceaseless quest for knowledge.

Go behind the scenes as Anthropocene’s creators share their inspirations behind the much-acclaimed project.

Synopsis

Act I

The research ship King’s Anthropocene is moored in northern Greenland. It is the end of the Arctic summer. Wealthy entrepreneur Harry King has financed a scientific expedition to collect samples from the ancient ice, which he hopes will reveal the origins of life.

With him on the ship are Professor Prentice, the expedition’s leader, alongside her husband Charles, both of them scientists. The crew comprises Captain Ross and Vasco, the ship’s engineer. They are joined by Harry King’s daughter Daisy, an amateur photographer documenting the voyage, and Miles, a journalist Harry has commissioned to report on the expedition’s triumphs.

While Charles, Daisy and Miles are away from the ship collecting samples, the temperature falls rapidly, the sea freezes, and the ship is in danger of becoming trapped in the ice. Prentice is determined to wait for those still away from the vessel but finally relents, even though it means abandoning her husband, and orders the Captain to cast off.

It is too late: the ship is trapped. Daisy, Miles and Charles return, bringing aboard a large block of ice. The rest of the expedition are amazed to see a body trapped within the ice block. When Daisy begins photographing the body inside the ice, she sees an eye move. Vasco takes an axe and smashes open the block. A young woman, Ice, is freed – alive.

The next morning, Miles uses the satellite phone to speak to his editor, explaining the extraordinary discovery – the story of the century! In the sick bay, Prentice, Charles and Harry King examine Ice and try to communicate with her. Slowly, Ice starts to speak. Miles’ editor wants him to keep high-profile tycoon Harry King trapped in the Arctic – in itself a front-page story. Miles agrees, and disables the communications system by removing a component. Ice escapes from the sick bay and runs into Miles on deck just as he is removing the component.

Later, Miles finds Vasco on deck as he tries to repair the communications system. They start fighting, and the vital communication component that Miles removed falls from his pocket. Vasco realises what Miles has done. In panic, Miles grabs a spanner and strikes Vasco on the head, killing him. He drags Vasco’s body off the ship.

Act II

Weeks have passed. It is the Arctic winter. Ice tells everyone that only blood will warm the water. Daisy believes she saw Vasco far away across the ice. Miles is alarmed that Vasco may not be dead, but Charles dismisses Daisy’s apparent sighting as an illusion.

Alone on deck, Miles decides it is time to call for rescue, since they are suffering too much. He is about to replace the missing component, but decides he will first pretend to have found it where Vasco supposedly dropped it. He will be seen as the hero, and save the day.

Act III

Prentice is haunted by her decision to wait for the expedition members out on the ice before leaving, meaning the ship became trapped. She tells her husband that she should have abandoned him, even though she loves him. Charles reminds her that the discovery of Ice will make them as famous as Newton, Darwin or Curie. Prentice fears that they will all die in the Arctic, and that nobody will hear their story.

A violent tempest breaks and King’s Anthropocene is crushed. Captain Ross suspects that Miles killed Vasco, but Miles denies the accusation, blaming Ice and claiming her presence will kill them all. Captain Ross turns on Ice, but Daisy defends her, saying it was they themselves who disturbed Ice by breaking her free.

Ice reveals her story. Her people had become isolated, their land increasingly frozen as the ice advanced. Her own family sacrificed her. Her blood melted the ice, made the water flow and freed her people. By taking her from the ice, the incomers have undone the original sacrifice. She tells them that another sacrifice must be made to set them free.

Miles produces the missing component, declaring that they are all saved since rescue can be summoned. Harry King is ecstatic, but as he grabs the component he drops it, and it shatters into pieces.

Their hopes are smashed. Miles confesses that he killed Vasco, but claims it was an accident. Prentice believes she must act to save everyone where she failed to act before, and so kills Miles. Ice is horrified by the savagery of their actions, pleading that a true sacrifice should not be like this. She leaves them, returning to the icy landscape.

The ice melts and the water flows. Rescuers are heard approaching.

Cast & Creative Team

Cast

Ice

Jennifer France

Professor Prentice

Jeni Bern

Charles, Prentice’s husband

Stephen Gadd

Miles

Benedict Nelson

Harry King

Mark Le Brocq

Daisy, Harry’s daughter

Sarah Champion

Captain Ross

Paul Whelan

Vasco

Anthony Gregory

Creative team

Conductor

Stuart Stratford

Director and Lighting Designer

Matthew Richardson

Associate Lighting Designer

Zoe Spurr

Set and Costume Designer

Samal Blak

Fight Director

Raymond Short

Movement Director

Kally Lloyd-Jones

The Orchestra of Scottish Opera

Mark Le Brocq as Harry King and Sarah Champion as Daisy in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Benedict Nelson as Miles and Paul Whelan as Captain Ross in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Sarah Champion, Stephen Gadd, Jeni Bern and Mark Le Brocq in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Jennifer France as Ice in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop. (3)

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Anthony Gregory as Vasco in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Jeni Bern, Jennifer France and Stephen Gadd in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Jennifer France as Ice in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop. (1)

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

The cast of Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Stephen Gadd, Jennifer France and Jeni Bern in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Mark Le Brocq as Harry King in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop. (2)

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Paul Whelan as Captain Ross in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Sarah Champion as Daisy in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Jeni Bern as Professor Prentice in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Jennifer France as Ice in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop. (2)

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Mark Le Brocq as Harry King and Paul Whelan as Captain Ross in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James Glossop

Jeni Bern, Paul Whelan, Mark Le Brocq and Anthony Gregory in Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2019. Credit James Glossop.

Anthropocene 2019. Credit James GlossopBreaking the Ice

Anthropocene’s composer Stuart MacRae and librettist Louise Welsh reveal the inspirations behind their icy operatic chiller.Stuart MacRae

Stuart MacRae has established himself as one of the most distinctive composers working today, writing music of elemental power and emotional subtlety. He is equally at home writing opera, orchestral music, chamber music and music for choirs, and his works take listeners on a journey through perceptions of nature, striking imagery and the landscape of human emotion.

His numerous staged works range from Echo and Narcissus, a dance-opera premiered in 2007 at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, through to the critically acclaimed The Devil Inside for Scottish Opera and Music Theatre Wales, written in collaboration with writer Louise Welsh. His previous work with Welsh for Scottish Opera, Ghost Patrol, won the 2013 South Bank Sky Arts Award for Opera and was shortlisted for an Olivier Award.

From 1999 to 2003 he was Composer in Association with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, and his works have been performed throughout Europe by groups including the Orchestre National de Lyon, Orchestre Philharmonique de Strasbourg, Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic, Scottish Chamber Orchestra, London Sinfonietta, Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, Scottish Ensemble, Hebrides Ensemble and Britten Sinfonia, by conductors including Martyn Brabbins, Oliver Knussen, Jan Latham-Koenig, Susanna Mälkki, David Robertson, Clark Rundell, Donald Runnicles, John Storgårds and Ilan Volkov.

Several of his works have been performed at the Edinburgh International Festival and BBC Proms, including his 2001 Violin Concerto which received its world premiere at the BBC Proms that year, and has been performed by Tasmin Little, Christian Tetzlaff and Tedi Papavrami.

His music has been recorded for NMC, Black Box, Delphian, Kairos and the London Sinfonietta’s own recording label.

Recent works include Cantata (2016) for the Choir of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, Piano Sonata No. 2 (2016) for Simon Smith, and Sunrises (2017) for the Gould Piano Trio. He wrote a series of works based on the Prometheus myth for East Lothian’s Lammermuir Festival.

Louise Welsh

Louise Welsh is the author of eight novels including The Cutting Room and The Plague Times Trilogy. She has written many short stories and articles, and is the author of four plays, most recently King Kiech inspired by Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi. Louise has edited volumes of prose and poetry, and has contributed to various journals and anthologies. She is the editor of Yonder Awa, a collection of poetry on the theme of Scotland and the North Atlantic slave trade by Scottish and Caribbean writers, and Ghost, a collection of 100 ghost stories from Pliny the Younger to James Robertson (Head of Zeus, 2015). Louise has presented more than 30 features for BBC radio, including Hellfire Nation (BBC Radio Scotland), Bannockburn Begins (BBC Radio 3) and Welsh’s Scottish Journey (BBC Radio 4). Other radio appearances include BBC Radio 4: Only Artists, Open Book, A Good Read, Saturday Review, Front Row, Woman’s Hour; BBC Radio 3: The Verb, Night Waves; BBC Radio Scotland: The Culture Café, Fred McAulay Show, Breaking the News.

Louise has received numerous awards and international fellowships, including an Honorary Doctor of Arts from Edinburgh Napier University and an Honorary Fellowship from the University of Iowa’s International Writing Program. In 2016 she was a University of Otago Scottish Writers Fellow at the Wallace Arts Centre in Auckland, New Zealand. Louise was also recently elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

In 2014 Louise was co-founder and director (with Jude Barber of Collective Architecture) of the Empire Café, an award-winning, multi-disciplinary exploration of Scotland’s relationship with the North Atlantic slave trade. The project was included in Glasgow’s Commonwealth Games Cultural Programme.

Louise has written librettos for three previous operas composed by Stuart MacRae, including the South Bank Sky Arts Award-winning Ghost Patrol and the critically acclaimed The Devil Inside. She is Professor of Creative Writing at University of Glasgow.

Benedict Nelson and Jennifer France in rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.

Benedict Nelson in rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.

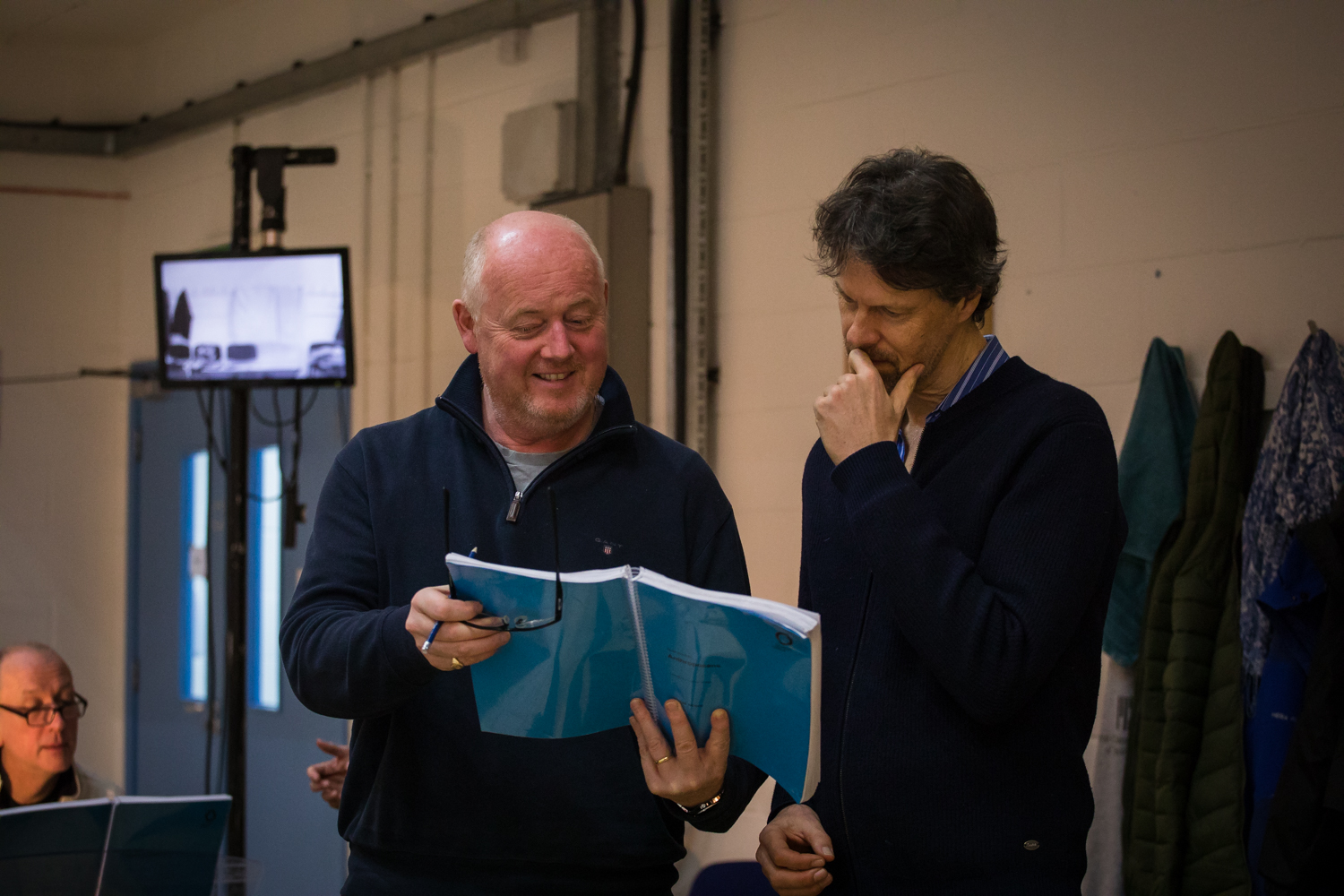

Director Matthew Richardson and Movement Director Kally Lloyd-Jones in Rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.

Jeni Bern, Director Matthew Richardson and Jennifer France in rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.

Mark Le Brocq and Paul Whelan in rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.

Mark Le Brocq and cast in rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.

Jennifer France and Jeni Bern in rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.

Jeni Bern and Jennifer France in rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd 2

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.

Paul Whelan in rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.

Jeni Bern and Jennifer France in rehearsal for Anthropocene. Scottish Opera 2018. Credit Nadine Boyd 3

Anthropocene 2019 in rehearsal. Credit Nadine Boyd.What the audience thought

Anthropocene: the creation of an operatic thriller

Composer Stuart MacRae and librettist Louise Welsh explore the themes of their chilly mystery opera with David Kettle

‘People can expect still to feel tense even after the opera finishes.’ Composer Stuart MacRae is unapologetic about the compelling narrative that he and librettist Louise Welsh have devised for their new work, Anthropocene. Indeed, there are undeniable thriller aspects to this tale of an unsettling discovery in the high Arctic – not to mention moments where the story could spin off in any number of alarming directions.

But alongside its unashamedly suspenseful storyline, Anthropocene is unafraid to engage with weightier issues – questions of climate change, sacrifice, even exploration and our ceaseless quest for knowledge.

MacRae and Welsh are both established creators in their own rights – MacRae as a widely commissioned composer, with BBC Proms and other festival premieres to his name; Welsh as an award-winning novelist and playwright, and also Professor of Creative Writing at the University of Glasgow. Anthropocene is their fourth – and most ambitious – collaboration for Scottish Opera, following the short Remembrance Day for the Company’s Five:15 season in 2009, then 2012 chamber opera Ghost Patrol (which won them a South Bank Sky Arts Award), and the Robert Louis Stevenson-inspired The Devil Inside in 2016.

Origins and inspirations

It was during the run of The Devil Inside that MacRae and Welsh first began discussing a new, larger opera. ‘The narrative element came first,’ explains MacRae. ‘We didn’t know where it would take place, but we knew our characters would somehow be confined together, and their relationships would start to break down. We talked about it being in a building, or a cruise ship. Then Louise brought in the idea of an outsider, a figure that would come into the group and be the catalyst for disruption.’

They point to specific works that were in their minds at the time, works whose influences can still be discerned bubbling under Anthropocene’s own distinctive identity. ‘I was interested in sci-fi films where the characters are confined in a spacecraft,’ remembers MacRae, ‘for example Alien or Danny Boyle’s Sunshine – the idea of isolating people where arguably there should be no people.’

Welsh points to two older texts as points of inspiration. ‘I thought a lot about Frankenstein,’ she explains, ‘particularly the ending where the Creature is left alone in the land of ice. We also thought about Shakespeare’s The Tempest, especially the idea of an island, and of strangers being introduced onto it.’

A film that exerted a particular influence, however, was the remarkable 2013 Danish documentary Expedition to the End of the World. ‘A group of people – scientists, an artist, a philosopher, a historian, an anthropologist – voyaged on a sailing boat to explore fjords in Greenland that had been locked in ice for millennia, but were now navigable because of climate change,’ explains MacRae. ‘That idea of a cast of characters with different reasons for being there, and who each look at their situation differently, fed into the narrative of Anthropocene.’

Why did they finally settle on an icy environment as their setting? ‘It’s just such an interesting landscape,’ says Welsh, ‘and one that’s made very dangerous by its extremes of weather. It’s a landscape that invites myths.’

‘Why does it invite myths?’ MacRae enquires.

Welsh offers a straightforward response: ‘Perhaps just because you can’t see properly! Lots of people have hallucinations on the ice – they see things that aren’t there.’ That’s an idea that has clearly informed Anthropocene’s unfolding narrative. ‘And of course we know of people who ended up in very extreme situations there, such as Ernest Shackleton.’ The Irish-born explorer’s 1914 expedition to cross the Antarctic led to the loss of his ship, Endurance, and three lives, before his party’s eventual rescue.

A balanced cast

With their setting decided, MacRae and Welsh’s next step, they explain, was to generate their characters. And here, there were practical as well as narrative concerns. ‘When you think about who would be on a research vessel in the Arctic,’ explains Welsh, ‘obviously there’s going to be a captain and crew – although our crew is much reduced – and the scientists involved. We thought it would be interesting to bring in the backer of the operation, too.’

It’s also the largest opera cast that MacRae and Welsh have created – eight singers, in a work that thrives on ensemble interactions rather than imposing a hierarchy of lead and subsidiary roles. And within the opera’s cast, there was an underlying intention behind MacRae and Welsh’s creation of characters: to provide strong, independent roles for women. ‘We thought: let’s level the playing field,’ explains MacRae. ‘The idea of a main female character in opera being a victim has been done so much. We wanted to look at the work as existing in the modern world, where we’re not just focusing on the adventures of men, with women as side characters. It was a conscious decision, but not a self-conscious one.’

Considering an outsider coming into this isolated group led MacRae and Welsh to contemplate unusual origins. ‘When we knew we were going to set the opera in the north of Greenland, and we talked about the idea of an outsider coming in, there had to be a supernatural element,’ remembers MacRae. ‘Otherwise who else could it be? There’s nobody else up there.’

‘There’s a mystery there,’ confirms Welsh. ‘Why is there a stranger there in the first place?’

Contemporary concerns

Despite its traces of magic and mystery, however, Anthropocene is very much an opera of our own times, and a work that refuses to ignore an issue that’s profoundly affecting the Poles: climate change. Welsh, however, is clear about the opera’s relationship with arguably the most pressing problem of our times: ‘This isn’t a “climate change opera”. But of course we’re aware that the human race is having an effect on the planet. We don’t have an answer, and the opera isn’t a finger-pointing exercise.’

‘Humankind’s relationship with nature and climate change are part of the context or the setting for the story,’ continues MacRae. ‘Because it’s set in the Arctic, which we know is at the forefront of the impact of climate change, it’s impossible to ignore that. Our characters acknowledge the issue, but they’re not presenting a vision – or our vision – of what needs to be done about it. We’d rather provoke people to ask themselves questions about climate change than try to provide answers.’

The opera’s title makes the work’s context explicit. 'Anthropocene' is an alternative term that’s been suggested for our current geological epoch (otherwise called the Holocene), in an unequivocal signalling that the most profound impact on the planet is coming from humankind itself. The term was first popularised in the early 2000s – many cite the work of Nobel prize-winning atmospheric chemist Paul J Crutzen, though the word existed for decades beforehand. It’s still an unofficial term, though scientists are increasingly confident about using it as an accurate, legitimate description of where we are.

In MacRae and Welsh’s opera, however, Anthropocene has another specific meaning. Entrepreneur Harry King, funder of the expedition, has co-opted the term as the name for his state-of-the-art research vessel. It’s perhaps a brash reappropriation of the word to indicate humankind’s dominion over the natural world, though the irony won’t be lost that King’s supposedly indestructible ship itself falls prey to unpredictable changes in the weather.

But the context of climate change aside, one of the opera’s underlying themes is sacrifice, an idea that plays out on different levels across the work, most clearly as an offering made to unseen forces to bring good fortune, but also in the subtler sense of willingly giving something up for the greater good. ‘We looked at myths and legends about sacrifice,’ explains Welsh, ‘and at Frazer’s The Golden Bough – we thought about early ideas that feed through into the Christian story.’

Welsh and MacRae also point to exploration – and ethical questions behind it – as an idea that informed the opera. Humankind might have the compulsion to voyage, explore and make discoveries, and indeed the technology to achieve it. ‘If we had enough money, we ourselves could go on one of these Arctic exploration trips,’ Welsh points out. But whether we should undertake these journeys, and disturb what we find there, is another question entirely. ‘The opera happens at the very top of the world,’ explains MacRae, ‘where arguably there should be no people. People have never lived there, and perhaps we should leave it alone.’

All the tension of a thriller

Anthropocene hovers somewhere between a realistic, true-to-life story and something more akin to a fable or allegory – though MacRae and Welsh are keen for audiences to interpret its narrative for themselves. The opera’s thriller aspects, however, are undeniable – something that both creators acknowledge. ‘Louise and I don’t really need to try to make a thriller,’ MacRae laughs. ‘It’s what we end up doing. What excites both of us, I think, is the sense of being able to build up tension, and to decide when to release it and how.’ Hence MacRae’s comment that audiences might leave the opera still feeling tense, and thinking about what they’ve just seen. ‘Louise’s novels are page-turners – I think it’s an instinct for both of us. I like music that’s tense as well – I know if I’m not feeling a bit wound up by a piece of music, then I tend to lose interest…’

Behind their intention to challenge and provoke, though, is MacRae and Welsh’s trust of their audience – to deal with sometimes challenging subject matter, and to engage with complexities in plot and music alike. ‘Stuart has a sophisticated musical language,’ says Welsh. ‘And the things we’re thinking about – the themes, the setting, the characterisation – are all quite challenging too. We have the respect for the audience that they can cope with that.’ She acknowledges, too, the expectations and prior knowledge that audience members themselves will bring. ‘That’s one of the joys of working with this kind of archetypal set-up. The audience will have seen films and read stories with a similar set-up, and they know it can go in any direction. So we’re working with the audience’s own expectations and imagination too.’

What’s equally important for Anthropocene’s two creators, however, is audience members’ experience in the theatre. ‘I remember a couple of people saying to me after The Devil Inside, that they weren’t sure if they liked it until the following day,’ explains MacRae. ‘I thought that was a great reaction, a real compliment, because it showed they’d been thinking about it.’

‘I love it when you go to the opera, or the theatre or cinema,’ says Welsh, ‘and you come out as though you’ve been on a rollercoaster ride, slightly dishevelled, with your hair all over the place. We want people to feel entertained and transported, and we want to make something that lives beyond the opera house, that steps out into people’s lives.’

What to listen out for

Character through vocal writing: MacRae provides distinctive vocal lines for the opera’s eight individual characters, using musical elements that reflect their contrasting characters. Captain Ross, for example, tends to sing in short, abrupt phrases that revolve around a limited number of notes, reflecting his solidity and perhaps a certain stubbornness. Harry King, by contrast, has expansive, confident vocal lines, while the mysterious Ice sings in high, unpredictable, sometimes decorated lines that convey her strange, volatile nature.

Musical set pieces: ‘How could you create an opera set in the Arctic and not use the northern lights?’ asks Welsh. And the shifting, kaleidoscopic hues of MacRae’s delicate setting in Act I form just one of the opera’s musical set pieces, alongside a raging storm that threatens the ship in Act III. ‘The storm is not all bangs and crashes,’ MacRae explains. ‘It’s more of a swell of sound. Sometimes composers focus on one sound world for a whole opera, but I tend to make a sound world or colour for each scene, often suggested by an image from the scene.’ Listen out also for the ship’s engines growling in the orchestra as they struggle ever more insistently against the ice near the start of the opera.

Tonality and non-tonality: MacRae integrates passages of consonant tonality into an otherwise more dissonant, non-tonal musical language. Tonal triads underpin several key scenes, and one particular passage in Act I is written in a modal minor key, standing out as strikingly different from the rest of the opera – intentionally so. ‘There is a section where for several minutes we’re in a tonal or modal world,’ MacRae explains, ‘and that’s a moment of self-realistion for one or two of the characters. It happens gradually, and it’s a very subtle transition into and out of tonality that contextualises this awakening.’

Flowing, cinematic structure: Within its three Acts, Anthropocene is divided into clearly defined scenes, but its structure might be experienced as more free-flowing, even cinematic. Music from one scene might stray into the beginning of the next, and MacRae and Welsh sometimes jump cut between contrasting conversations within a single scene.

Instrumental colour and quartertones: Quartertones – musical pitches that fall in the cracks between notes on a piano keyboard – provide a rich, unusually ear-tweaking sound world for certain scenes in the opera. Up high on violins or piccolo, they add a strange sparkle to the opera’s sound, and the incessantly shifting microtonal harmonies make a striking effect at Anthropocene’s conclusion. MacRae further adds to the opera’s arresting sonic universe with some very unusual percussion instruments, used sparingly but to great effect.

David Kettle is Scottish Opera’s Programme Editor. He is also a music critic for The Scotsman and The Daily Telegraph, and has written about music for a broad range of publications including Classical Music, The Strad, The List, The Times and BBC Music Magazine.